The Battle for The Bears Ears, Part III: Road Wars

This is the third installment of a series of articles examining protection of Cedar Mesa and the proposed Bears Ears National Monument.

On Christmas Day of 1879, George B. Hobbs gazed out over Cedar Mesa to contemplate his fate. Along with three other scouts from the Hole-in-the-Rock Expedition, Hobbs found himself without food, on a planned eight-day reconnaissance that had somehow turned into a 23-day ordeal. Hobbs later wrote that the snowy desert landscape “Surely looked like [where] our bones would bleach.”

Hobbs’ companion and Expedition Captain Platte D. Lyman described the surrounding wilderness:

The country here is almost entirely solid sand rock, high hills and mountains cut all to pieces by deep gulches which are in many places altogether impassable. It is certainly the worst country I ever saw, [but] some of our party are of the opinion that a road could be made.

Faced with a painful death from starvation and exposure, it’s hard to imagine the group focused on anything beyond immediate survival. Yet even in those desperate straits, they thought about building a road.

It wasn’t until the 1940s that their vision became reality, when the route they forged across Cedar Mesa was developed as Utah State Road 95. It would have come as no surprise to the Hole-in-the Rock Pioneers that 95 was rough and difficult, with rocks, sand, and frequent washouts. The 80-mile trip from Blanding, Utah, to Hite Crossing on the Colorado River could take two full days.

Utah 95, descending the west side of Comb Ridge

Utah 95, descending the west side of Comb Ridge

Despite the challenges of travel, 95 was nonetheless a vital lifeline to local residents, the first permanent road in San Juan County to run west. Recognizing its value, the State of Utah paved it in the 1970s, dynamiting a new passage through Comb Ridge. Although most local residents could not imagine anyone objecting to the upgrade (it is now possible to drive from Blanding to Hite in about 1.5 hours), at least one person thought otherwise.

Edward Abbey wrote his most famous novel, The Monkey Wrench Gang, as a polemic response to the paving project. In a key scene, George Hayduke and his band of environmental outlaws perch on the crest of Comb Ridge and observe a construction crew at work:

The little pinyon pines and junipers offered no resistance to the bulldozers. The crawler-tractors pushed them all over with nonchalant ease and shoved them aside, smashed and bleeding, into heaps of brush where they would be left to die and decompose… Behind the first wave of bulldozers came a second, blading off the soil and ripping up loose stone down to the bedrock.

Where many would see progress, Hayduke and his friends can only see the violation of the land. Hayduke’s outlaws sabotage the bulldozers in an overnight raid, a futile attempt to preserve the area as “Roadless, uninhabited, a wilderness… [to] Keep it like it was.”

Graffiti on Comb Ridge, a tribute to Edward Abbey’s fictional George Hayduke

Graffiti on Comb Ridge, a tribute to Edward Abbey’s fictional George Hayduke

The worldviews of Hayduke (an obvious stand-in for Abbey) and the typical San Juan County resident were 180 degrees apart, but there was one thing on which they would agree: wilderness requires the absence of roads. Wilderness is nature untouched by man; roads are the hallmark of civilization.

Forty years later, the battle between roads and wilderness rages on, and Cedar Mesa is still ground zero.

Road on Cedar Mesa, below the Tables of the Sun

Road on Cedar Mesa, below the Tables of the Sun

A host of BLM signs across the landscape restrict drivers to “Designated Roads Only.” To most readers, a subtle anomaly in the signs would pass unnoticed; the word “Designated” has been carefully pasted over the word “Existing,” written in an alternate font. But in the desert southwest, where today’s ATV tire tracks become tomorrow’s existing road, the difference is momentous.

BLM road sign along Butler Wash

BLM road sign along Butler Wash

By limiting traffic to designated roads, the BLM is asserting itself as the legal arbiter of what counts as a road – and sole owner of any that make the cut. Vehicles can only go where the BLM allows; everywhere else is off-limits, whether a road goes there or not. In some cases, that can mean the loss of routes established almost as far back as the Civil War, before Utah was even a state.

In 1866, thirteen years before the Hole-in-the-Rock Mormons set out on their arduous journey, Congress passed a law granting settlers “The right-of-way for the construction of [roads] across public lands.” The law, known as Revised Statute (R.S.) 2477, was designed to encourage development across the vast frontier of the American West.

The law stood until 1976, when it was repealed by Congress in the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA), signaling an end to the official policy of homesteading and a formal recognition that the western frontier had long since closed.

However, as historian Jedediah S. Rogers explains in Roads in the Wilderness: Conflict in Canyon Country, any road built under R.S. 2477 could revert to local county ownership if it “Had been constructed beyond the mere passage of vehicles and had been in continuous use… prior to 1976.”

In the State of Utah, most of the affected routes (many little more than faded Jeep tracks) were in three southern desert counties: Kane, Garfield, and San Juan. The counties laid claims to tens of thousands of these roads (4,000 miles in San Juan County alone) expressing their desire to keep them open and under their immediate control.

San Juan County road marker, below the Abajo (Blue) Mountains

San Juan County road marker, below the Abajo (Blue) Mountains

However, Congress only recognized a small percentage of those roads as having valid R.S. 2477 rights, spawning an endless stream of legal conflict ever since. The discord has been particularly virulent in places where Federal Wilderness designation might result.

In September of 1996, President Clinton used his authority under the Antiquities Act to establish Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. One month later, aggrieved Kane County protestors were suspected of “Taking bulldozers and scrapers and widening all two track jeep roads to deliberately hijack the [monument’s] wilderness characteristics,” according to Rogers.

In San Juan County, Arch Canyon has been a R.S. 2477 flashpoint for decades. Long a popular destination for off-road vehicle (ORV) use, the BLM attempted to close the canyon to vehicles in the 1970s.

Arch Canyon

Arch Canyon

However, enforcement was sporadic or nonexistent and the road remained open under a contested R.S. 2477 claim. In 1989, the Jeep-Chrysler Company held its first annual Jeep Jamboree at Arch Canyon, but the company moved the following year’s event elsewhere to avoid becoming embroiled in the ongoing controversy. The result was a convoy of vehicles driven up the canyon in protest against the BLM, with the ORV enthusiasts hoping to solidify the road’s existence by driving on it.

A similar scene played out in May of 2014, just outside of Blanding, Utah. San Juan County Commissioner Phil Lyman led an all-terrain vehicle (ATV) protest ride into Recapture Canyon, another disputed R.S. 2477 way. Among the participants were Ryan Bundy and Ryan Payne, two key figures in both the Bundy Ranch Standoff with Federal Law Enforcement Officers in Nevada in April, 2014, and the more recent Malheur Wildlife Refuge Occupation in Oregon in January, 2016.

Although no armed standoff resulted at Recapture, tensions on the day ran high as a parade of ATVs motored through a crowd of conservation-minded onlookers. County Commissioner Lyman, a self-described “Rosa Parks” of public land use, was eventually sentenced to 10 days in jail, 3 years of probation, and a possible fine of close to $100,000 for damage to archaeological sites caused by the protest.

Lyman remains unbowed; the perceived stakes of losing the use of the road are just too high. He doesn’t just share a name with the earliest San Juan County settlers, going all the way back to Platte D. Lyman and the Hole-in-the-Rock Expedition, he shares their attitude: roads are as important as survival.

It was those Hole-in-the-Rock Settlers and their descendants who developed the roads in the original spirit of R.S. 2477, opening up the difficult landscape for both economic and recreational use. As County Commissioner, Phil Lyman currently represents voters whose taxes pay to keep countless secondary roads open and passable – no minor commitment in the sparsely populated region.

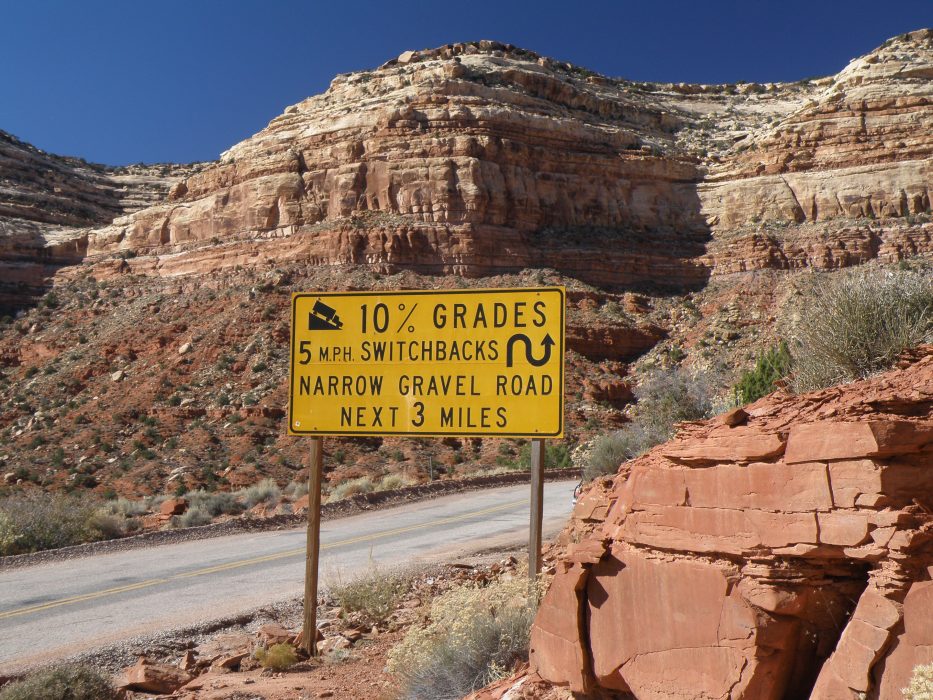

Utah 261, approaching the switchbacks of the Moki Dugway

Utah 261, approaching the switchbacks of the Moki Dugway

For many of those San Juan County citizens, the loss of any roads to a Bears Ears National Monument would be particularly galling and undoubtedly seen as evidence of the federal government trampling on rights they’d held for generations. The birth of the monument might well be greeted with bulldozers and other vehicles driven across the land in protest – if not with active armed resistance.

But this should come as no surprise; conflict is written right on the landscape. The Bears Ears Buttes are literally bisected by a road, split down the middle by an access route to Elk Ridge. One of that road’s informal spurs leads to the rim of Lyman Canyon, and a second leads to a viewpoint over Arch Canyon. The heart of the battle is right there for all to see, even without a road sign.

Read the entire The Battle for The Bears Ears series:

- Part I: The Legislative Landscape

- Part II: The End of Obscurity

- Part III: Road Wars

- Part IV: The Trouble With Archaeology

- Part V: A Personal View