The Mountain Zone – A Look Back

The call arrived via one of our satellite phones just as I got to work the morning of May 2, 1999. Routinely, we routed the Everest calls through a special number at MountainZone.com with equipment that recorded every one and alerted me and my editorial staff to incoming news. On the other end of the scratchy call, I recognized the laconic voice of Eric Simonson, expedition leader.

It was 8 p.m. in the Himalaya, so the search day high on the Tibet side of Everest would be over and the climbers back in high camp. The search for missing British climber George Mallory was scheduled to last for a week, so I wondered why Eric would be calling now. I soon found out.

“Are you sitting down?” he asked from his tent in base camp. I felt the adrenaline starting to build and reverberate within me before asking, “Oh come on, don’t tell me you found Mallory? No way.”

“Yep,” he said. “Conrad found him. You’re the journalist guy, so you’re going to be busy. And you’ll need to be in Kathmandu for the press conference when we get there in about a week. We’ll try to send a picture tonight as proof. Nobody, not even us, can believe it.”

Related: Read the original 1999 Mallory & Irvine Research Expedition coverage

The finding of George Mallory’s body, after the English climber had disappeared 75 years earlier on Mount Everest, was about to become the first major news story ever to be broken on the web. MountainZone.com had sponsored the Mallory and Irvine Research Expedition, so they became the medium by which the story got out. Nobody really expected to find the missing British climber. We had signed on because it was a new and fascinating story, a way to feed the raging mania about Everest in the late 90s.

“Nobody really expected to find the missing British climber.”

But Dave Hahn, Conrad Anker, and the other climbers led by Eric had, against all odds, found George Mallory’s body, preserved by cold so well you could make out the contours of his tricep where his tweed clothing was torn as he lay face down on the slope.

I went to Chris Helms, our tech lead, and told him the servers were going to melt down when we went live with the story mid-morning. They did, but somehow Chris managed quickly to route us through a big server farm and keep us live as we clocked a million hits per hour.

What ensued over the next week was a frenzy. MountainZone was on page one of every English-speaking newspaper in the world. Our communications director, Meredith Goldstein, told me, “Your life is over for a while,” and started putting Post-It notes on the glass door of my office in Seattle to alert me to incoming media: BBC 3 at 1 p.m., ABC at 1:30, South African Television at 2, The New York Times at 2:30, NBC at 3. And so it went. For days. I got a thousand emails a day and actually had to hire someone to read them all.

MountainZone.com was born in the quiet early days of the young dot-com industry in 1996 but was about to make major noise. It’s not an overstatement to say the nascent site was on the cusp of changing how the world viewed the “web,” which was still a backwater, experienced by most people on tedious and glacially slow dial-up connections. For a site that the New York Times later would say “made a spectator sport out of Himalayan climbing,” the timing for MountainZone.com was perfect. Coming on the heels of the climbing disaster on the Nepal side of Everest that same year, the events made famous by Jon Krakauer’s book Into Thin Air; the world was hungry for news of Everest and high altitude climbing in general.

Jon Krakauer’s epic account of the May 1996 tragedy on Everest.

Jon Krakauer’s epic account of the May 1996 tragedy on Everest.

MountainZone.com was ready. The staff pioneered the use of satellite phones to cover major expeditions live. Nobody else at the time knew how to do it, not even the companies that made the phones. We would ask the phone manufacturers if the devices were data capable, and after an awkward pause, the answer was, “We don’t know.” But our tech staff figured out how to do it, and the day they found Mallory, Dave Hahn stayed up all night squeezing a tiny 100 kb image of George Mallory’s body through that pre-historic sat phone. Data indeed. We had our proof. We put a watermark on it and went live. The world went nuts.

The body of George Leigh Mallory, photographed Saturday, May 1, 1999 at 27,000 feet by members of The Mallory & Irvine Research Expedition.

The body of George Leigh Mallory, photographed Saturday, May 1, 1999 at 27,000 feet by members of The Mallory & Irvine Research Expedition.

Never mind Sir Edmund Hillary called us “ghouls and grave robbers,” and the iconic British climber Chris Bonington said worse. But how can you break news like that without showing your viewers proof? That story proved the concept of immediate and high-quality niche journalism courtesy of the “information superhighway.” At the advertising agency in LA that bought the Mallory expedition sponsorship for Lincoln, they drank champagne.

Early Days

In the late 90s, a strange and entirely new phenomenon was spreading like a prairie fire across the civilized world: the Dot-Com Boom. Odd, new retailers named Amazon.com and Drugstore.com were coming online, and content sites, such as the highly regarded Salon, appeared the equal to any print product but available only online. Among them, perhaps most unlikely of all, was MountainZone.com. In a few months the site would change the paradigm about reporting on mountain sports from climbing to snowboarding, skiing, and mountain biking.

In some ways, the site was destined for glory. Founded by Skip Franklin, Todd Tibbets, and Greg Prosl, MountainZone.com was an inspired idea: a way to deliver mountain sports online with an immediacy that rivaled television. The first event they covered was the US Snowboarding Championship in Vermont in March 1996.

But the success or failure of the site was unclear; its trajectory was as clouded as that of the internet that delivered it. No one even knew if the “web” would catch on. That sounds ridiculous now, but at the time it was a fact. It was an accident of timing that first gave MountainZone.com the Saturn V solid-fuel booster it needed to reach escape velocity through mega traffic – the Everest tragedy of 1996.

I was asked to join MountainZone.com as editor in the spring of 1996, just as the news of Scott Fischer’s death trickled slowly back to Seattle. At the time, despite the presence of a few early sat phones, news from Everest was delivered mostly by porters and climbers trekking back from base camp to Namche Bazaar. A week delay was common and rumors and misinformation were rife. Slowly, the truth of that deadly storm on May 10, 1996, got back to civilization, just as MountainZone was gearing up.

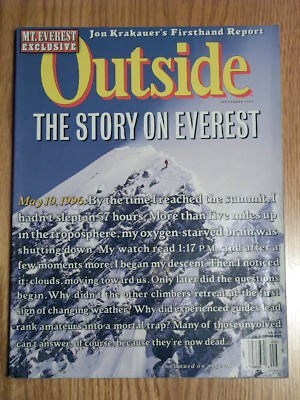

The Zone’s first major traffic success came when Krakauer’s story of the tragic climb was published by Outside Magazine. Earlier that year, I had interviewed Anatoli Boukreev, one of the Mountain Madness guides working with Scott Fischer during the tragic climb, and quickly received a call from him after the article ran. Anatoli wanted to rebut some of the points made about him in the article, but Outside said he could only have 200 words in the letters-to-the-editor section. I told him he could have all the words he wanted on MountainZone.com, so Anatoli wrote up his version of events on that fateful climb. We posted the piece.

Anatoli’s story became one of the first high-traffic events for the fledgling site. Millions tuned in and I was amazed how the heretofore arcane world of Everest had suddenly entered the mainstream. Then I got a call from Krakauer, who was an acquaintance of mine and might have even been considered a competitor in the insular world of adventure journalism. Jon told me he could not let Anatoli’s views go unchallenged, so I said fine. We’ll start a conversation. Jon sent me his response to Anatoli, and the world came to MountainZone to hear that dialogue. We were made.

Related: The Untold Story of the 1996 Everest Tragedy

In the early years, Himalayan climbing was our specialty, featuring live “cybercasts” of Everest every spring, while also following other important climbs on the 8,000-meter peaks. Ed Viesturs reported live on every attempt he made trying to climb all 14 of the world’s highest peaks without supplemental oxygen.

Looking for something more interactive, I followed up the journalism we did after the 1996 tragedy by going to Everest myself to report on the following year’s climbing season in real time. My friend Todd Burleson owned Alpine Ascents International, one of the first guide services to lead climbers to the top of Everest for a fee. I would tag along on AAI’s 1997 Everest Expedition so that MountainZone.com could report daily – even hourly on summit day – during the six-week course of the expedition.

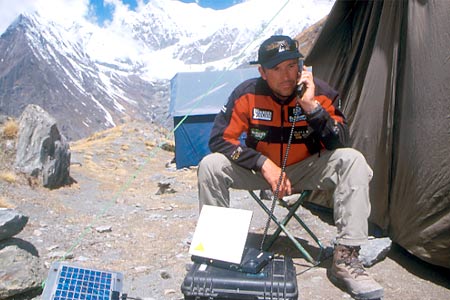

That was the trip that really gave us the whammy on sat phones, the only device on which this kind of journalism could be done. When we couldn’t get them to work from the rooftop of the Yak and Yeti Hotel in Kathmandu, we got serious about figuring them out. Sat phones were the key in the early days; the technology that actually made the journalism possible. First, I reported on the 1997 trek into Everest, later we did daily dispatches during the successful climb by guide Wally Berg.

At the time, we used Inmarsat phones zeroed in on the Indian Ocean satellite in geosynchronous orbit. I’d get to a teahouse in Namche Bazaar or Thyangboche, find a south-facing window, preferably upstairs, and call in the dispatch. Or when we were camping, we’d find a place, like Sonam’s tea house in Dingboche, apply the clamps to the 12-volt motorcycle battery Sonam used to power his one light bulb, and send the dispatch. The locals helped us out. We felt unstoppable. Traffic was through the roof.

Glory Days

With sponsorship dollars pouring in, along with venture capital, we had the resources to expand our coverage. I began building a content staff, careful to hire smart young people new to journalism, some right out of school. We were going to build something totally new and I didn’t want old hidebound ideas from print or broadcast journalism to hold us back. So we made it up as we went along.

We kept a strong focus on Himalayan climbing. MountainZone.com not only produced live “cybercasts” from Everest every spring, but reported on other climbs as well. Climber Ed Viesturs was on a quest to climb all 14 of the world’s 8,000-meter peaks without oxygen and become the first American to do so. We gave him a sat phone and let him share with the world the epic struggles as he ticked off the world’s greatest mountains: Makalu, Broad Peak, Manaslu and Dhaulagiri (both in one year), and finally Annapurna.

Ed calling in a dispatch from Annapurna basecamp.

And we broadened the scope of mountaineering coverage by sending Wally Berg and Dave Hahn to report on climbing the Vinson Massif in Antarctica. Our audience was fascinated. We followed a team of crazy Russians who climbed Denali in full-on winter. “We climbed it like mice,” they reported, digging in deeply, living underground, and scurrying higher only as conditions allowed.

Willi Prittie descending Vinson Massif, Antarctica, December 1999.

With a half-dozen editors, each focused on a specific sport—including snowboarding and mountain biking—MountainZone.com became one of the first journalistic outlets to report professionally on these new activities that resonated with a genuine outlaw vibe. Snowboard editor Hans Prosl’s request for media credentials was turned down by the Olympic Committee for the Nagano winter games, so he went anyway. Sleeping in rental cars, climbing under and over fences, dodging officials, he saw to it that MountainZone’s coverage of those first snowboarding Olympic events was second to none.

Ski editor Michelle Quigley Pearson came to us after ski bumming in Jackson Hole a few years, and her connections soon paid off. She skied in Valdez with Shane McConkey and Alison Gannett before they were household names. She got radical film clips from helicopters and the first coherent interviews with these iconoclastic athletes. Michelle covered the Freeskiing World Tours in ’98 and ‘99 from crazy cliffside courses in Snowbird, Whistler, and around the West.

She sent Scot Schmidt to Mt. Belukha in the Altai Mountains of Siberia to cover the first ski descent via satellite phone. MountainZone partnered with Warren Miller to sponsor his annual films and feature other content from that organization. And, we embarrassed mainstream media by covering the World Cup Alpine Skiing competition and the Olympic ski races with brashness, flair, and a twisted sense of humor.

Schmidt descending Mt. Belukha, April 1999.

MountainZone.com was everywhere news was being made in the mountains. A staple for us were the video interviews I did with the world’s best climbers. Greg Child, Lynn Hill, Alex Lowe, Mark Twight, Jim Wickwire, and dozens more all did live, in-person video interviews from our own studio in Seattle. For the first time, people who had begun following climbing on the heels of Krakauer’s book got a glimpse into the character of these climbers who were making history with first ascents around the world.

I did an interview with Anatoli Boukreev in 1997, in Kathmandu, shortly before he was avalanched and killed on Annapurna. It remains the only English language interview with, perhaps, the pivotal figure of the Into Thin Air tragedy.

The site had come to prominence with our pioneering coverage of Everest climbs, and the once-or-twice-yearly cybercasts from that storied peak remained the highest traffic stories we did. Each Everest expedition was different, but few matched the astonishing news of the team that found Mallory in 1999.

I strolled into the office of the MountainZone CEO, and said, “I need fifty grand by Thursday to lock this down.”

It is a reflection of the time that when Eric Simonson offered me the opportunity before the search to co-sponsor his expedition with the BBC, I strolled into the office of the MountainZone CEO, and said, “I need fifty grand by Thursday to lock this down.” Chuck looked up and asked, “Will they find Mallory?” I said no, but it will make a great story and people will love the history. He said yes to the money.

So there we were, a bunch of scruffy weirdos who followed no rules and thought everything was possible, in partnership with the BBC. It beggars belief. In retrospect, like soldiers reminiscing over the big battle, there are too many unforgettable stories to tell from those magic years, 1997-2000.

Sadly, we reported on a lot of tragedy—it is an unavoidable aspect of mountain sports. It all hurt, but nothing came close the pain of the 1999 Shishapangma Expedition, a trip we sponsored for Alex Lowe so he could make the first ski descent of the 8,000 meter peak in Tibet. It was meant to be a lark, a fun trip with his friends Andrew McLean, Conrad Anker and a few others. We would cybercast it live; The North Face would make a movie.

Coming off the heels of Lowe’s historic first ascent of Trango Tower, this was envisioned as a low risk climbing trip to feature a different side of Alex, who was widely regarded as the best climber in the world. The team was having a ball. They sent photos of them eating ramen with Lost Arrow pitons and drinking whiskey from food bowls. It was like a climbing trip in the Rockies or Cascades with friends, only it was on an 8,000 meter mountain in the deep Himalaya.

Alex Lowe eating Top Ramen with a piton during the 1999 Shishapangma Expedition.

It is fitting, I suppose—since much of MountainZone.com content came to us and then to the world over a satellite phone—that the news of Alex’s death came in another morning call, about 8 a.m. on October 5, 1999. Andrew McLean called me from the Shishapangma base camp to tell me that Alex and photographer Dave Bridges were buried by a huge avalanche that only barely spared the life of Conrad Anker.

Was MountainZone fanning the flames by glorifying risk?

For me, it was a punch in the gut. I was losing my ability to put distance between the death of my friends and my own psyche. First, Scott Fischer dies on Everest. Anatoli dies on Annapurna. And now Alex, with whom I had become friends through interviews and cybercasts, was taken in a random act. I had to deal with it. I was going to have to write the story, and the headline, that Alex was gone. I actually questioned what we were doing. Was MountainZone fanning the flames by glorifying risk?

On reflection, I don’t think so. We were just there, in an accident of time and space, so MountainZone.com was the perfect medium to get out the news because we got it right. We opened up that secretive world of extreme mountaineering and extreme sports to everyone. The death of Alex Lowe in a way symbolized the end of a more innocent era of big time mountain sports. When I heard the news a few months ago, I found solace in the fact the bodies of Alex and Dave were found in early 2016, bringing that tragic episode full circle.

Final Days

The Shishapangma tragedy marked the end in more ways than one. MountainZone.com was sold shortly after to a San Francisco-based internet company that, in my opinion, did not understand what the site was about. They layered on a corporate structure to our unruly band, and brought in “story tellers” to, in my opinion, over dramatize the expeditions and events we covered. For the first time something false was placed between the immediacy of the action and the audience that loved it. It was wrong. I left as soon as I got my climbers safely off Everest and the rest of the staff was not far behind me. MountainZone.com would go off the air months later.

The ride was over; I was wasted. I was actually considering a ranch in Patagonia, but the millions we had dreamed of vanished as quickly as they’d appeared, perhaps the only logical end game to the nutty Dot-Com Boom. We shrugged it off. The thing was not about making money, it was about making the most of an opportunity that comes at the intersection of vortexes: the internet, satellite communications, and the backing to do almost anything we could dream.

Now, every Everest climber has a web site and a sat phone – a good one – unlike the ones we used. It’s all a little ironic as they are not even necessary because you can get a cell signal right up to the mountain. MountainZone.com’s salad days spanned the blink of an eye, a brief golden moment like the fiery climax of a meteorite before impact. But it was outrageous, it was important, and it was fun.

But now, 20 years from its inception, MountainZone is coming back. It will no longer be just a footnote of the internet’s infancy; it will be a living, breathing site, ready to, once again bring the adventure, exploration, and wonder of the mountains to readers around the world. I’m excited to see what they have in store.

Peter Potterfield, author of High Himalaya, In the Zone, Classic Hikes of the World, and a dozen other books, served as editor and publisher of MountainZone.com from May 1996 to June 2000.

Peter Potterfield, author of High Himalaya, In the Zone, Classic Hikes of the World, and a dozen other books, served as editor and publisher of MountainZone.com from May 1996 to June 2000.