The Battle for The Bears Ears, Part IV: The Trouble With Archaeology

This is the fourth installment of a series of articles examining protection of Cedar Mesa and the proposed Bears Ears National Monument.

When it comes to protecting the land, archaeology is the problem from hell. Ruins deteriorate and crumble away, vulnerable to animal disturbance, erosion, and weathering. Looters and vandals can destroy sites just as easily as the respectful visitor. A single careless footstep can crush an artifact, shift a wall foundation, or despoil a midden. Casual fingerprints on a pictograph can leave irreparable damage.

Ruin at Cedar Mesa

Ruin at Cedar Mesa

The problem is particularly acute in the desert of southeast Utah. This region, what author Craig Childs calls “An archaeological mecca, one of the richest zones in North America,” harbors thousands of burial sites, rock art panels, and abandoned settlements, all in unsecured wilderness. At the heart of this landscape lies the Bears Ears.

If the land is left in its current state, problematic trends will continue unabated into the future. The Internet will lead multiplying visitors into the backcountry and the remaining archaeological resources will continue to degrade through casual contact, looting, and carelessness. Eventually, every rock art panel will be vandalized, every artifact will be stolen, and every grave will be plundered.

Pictographs at Cedar Mesa from Archaic period (6500 BC – 1500 BC)

Pictographs at Cedar Mesa from Archaic period (6500 BC – 1500 BC)

The desire to avoid this dispiriting outcome has led to calls for creation of a Bears Ears National Monument. But this solution confounds the problem of protecting the archaeology with protection of the land itself. Protecting the land is necessary, but not sufficient. At the same time, implementing the measures required to protect the archaeology in full would weaken or destroy other valuable qualities of the land. This leaves land managers facing an impossible dilemma and monument proponents facing an undesirable outcome, even if they achieve the legislation they seek.

Monument advocates should examine other parts of the canyon country for clues as to how the situation will play out. Although it hasn’t been proposed for Bears Ears, creation of a National Park would provide the strongest federal land protection currently available. The result might look similar to Colorado’s nearby Mesa Verde National Park.

Boulder with pictographs at the foot of Cedar Mesa

Boulder with pictographs at the foot of Cedar Mesa

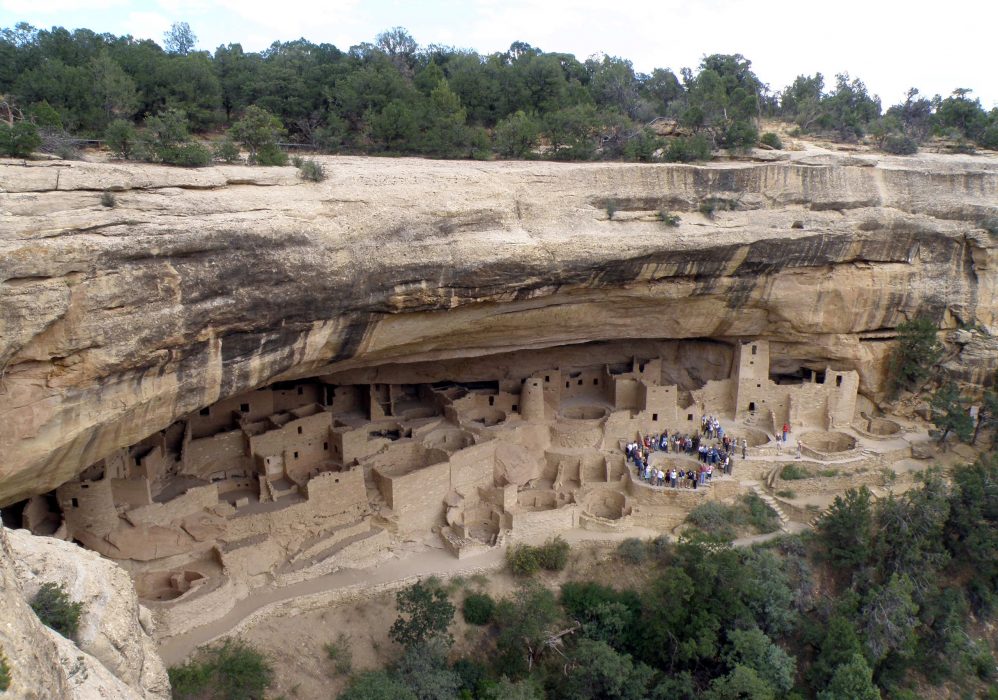

Mesa Verde’s commitment to protection is ironclad, using an approach that might be called “Fortress Archaeology:” a handful of relics are displayed in the museum, visitors can only access the park’s magnificent cliff dwellings on a guided tour, and the public is forbidden from entering the backcountry altogether.

The vast majority of Mesa Verde’s artifacts are stored in a sealed warehouse, secured from ravaging forest fires and other natural disasters. This keeps them safe, but it also keeps them out of view. As Craig Childs points out in his book Finders Keepers: A Tale of Archaeological Plunder and Obsession, “Institutional storage rooms are available to anyone with the credentials to gain access,” but the only people with the right credentials are the archaeologists who have thereby “Proclaimed themselves the rightful stewards and recipients of the past.”

To many, this seems like a betrayal. The public cannot see these artifacts, despite their collection from nominally “public” land. Interested visitors are treated only as interlopers and threats. The same principle holds true in the park’s restricted backcountry, where it is next to impossible for the layperson to get a permit.

Collected pottery at Edge of the Cedars Museum in Blanding, UT

Collected pottery at Edge of the Cedars Museum in Blanding, UT

The “Fortress Archaeology” approach at Mesa Verde is effective in preserving the park’s cultural heritage, but calls into question the very meaning of public land. Although the park matches the legal definition, “land held by the government,” the spirit of public land – the idea of land belonging to all of us – is conspicuously absent.

At Bears Ears, where the BLM currently manages much of the landscape under its “variety of uses” doctrine, loss of almost all public access would be particularly egregious. Even if a National Park was proposed, the “Fortress Archaeology” approach is unthinkable.

The highest type of land protection that is actually recommended for Bears Ears is federally designated wilderness, which would offer some clear benefits. The types of industrial uses that wilderness forbids are threats to archaeology as well; machines like bulldozers, chainsaws, and road graders can wreak havoc on the landscape in many ways. Even now, large parts of the canyons are physically inaccessible to motorized access or are parts of existing Wilderness Study Areas, yet sites located there are already under threat.

Tour group with ranger at Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde National Park

Tour group with ranger at Cliff Palace, Mesa Verde National Park

Worse, just as the visitor restrictions at Mesa Verde bring into question the idea of public lands, full archaeological protection at Bears Ears would defeat the notion of wilderness.

To keep the archaeological resources safe would require vast teams of rangers to police visitors’ every move. Even if such an approach were feasible, the general idea of wilderness – a land “where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain”– would be rendered meaningless if a patrolling ranger lurked around every canyon bend.

This scenario also has no connection with the current environment on Cedar Mesa, where much of its appeal lies in the possibility of traveling for days in the backcountry without seeing another person.

Pictographs on a boulder above the San Juan River

Pictographs on a boulder above the San Juan River

With neither National Park status, nor sufficient resources to secure the wilderness possible, the likely model for the future of the Bears Ears is Canyons of the Ancients National Monument. Established along the Colorado–Utah border in the face of heavy local opposition, Canyons of the Ancients, much like Bears Ears, was previously BLM land and was created to protect one of the most archaeologically rich areas of the United States.

The land status changed with the birth of the monument in 2000, but the funding did not. Despite the new legal structure and formal recognition by the federal government of the importance of the land, the budget for backcountry protection by paid rangers and archaeologists was left unchanged. A team of volunteer site stewards attempted to fill the vacuum, but the vast majority of archaeological sites are left out of the program; there are simply too many to cover. In effect, the site stewards are able to hopelessly monitor the deterioration of the cultural resources but lack sufficient power to prevent it.

At Bears Ears, a new monument seems similarly unlikely to warrant any new funding. Even with a moderate budget increase, the best approach to protection might be the implementation of a type of salvage archaeology. A select group of front-country “sacrificial” sites would be fully excavated and stabilized, ready to receive the public. The other thousands of backcountry sites will remain in their current state, accessible to the intrepid explorer and still subject to the deterioration and damage that even well-meaning visitors can provide. Maybe some volunteer rangers will document the inevitable destruction.

That is not the outcome proponents of a Bears Ears National Monument are seeking, but it may well be the one they get. A National Monument sounds impressive, but as a retired government archaeologist pointed out, “Changing the name is only advertising, not help in protection. It’s not difficult to get on board with a political movement for the monument, the trick is dealing with the consequences. What are you going to do next? That’s harder.”

Hard enough to be the problem from hell.

Read the entire The Battle for The Bears Ears series:

- Part I: The Legislative Landscape

- Part II: The End of Obscurity

- Part III: Road Wars

- Part IV: The Trouble With Archaeology

- Part V: A Personal View