The Battle for The Bears Ears, Part V: A Personal View

This is the fifth and final installment of a series of articles examining protection of Cedar Mesa and the proposed Bears Ears National Monument.

On my first day as a ranger I climbed the Bears Ears. Visible more than 100 miles away from my home in New Mexico, they stood like two beacons above the desert, impossible to resist. After checking into the station at Kane Gulch, there was no question where I was headed next.

The climb was unpleasant, a thorny bushwhack on loose dirt and rock. Multiple lines of barbed wire blocked the way and a deceptive sign at the saddle had misidentified which ear was the highest, requiring an embarrassing descent and a second climb to reach the true summit.

The view from the top made it all worth it. To the north, the high alpine country of Elk Ridge and the Dark Canyon Wilderness stretched to the snow-covered Abajo Mountains. To the south, the great tableland of Cedar Mesa was laid out like a map, exposing the secret hidden in plain sight at ground level. The mesa was not flat, but tilted away on either side of the central spine. Over millions of years, water flowing down both sides of that slope had carved the mesa’s rich sandstone canyons.

Side canyon on Cedar Mesa

Side canyon on Cedar Mesa

Gazing down on those canyons, it was impossible not to think of the unlikely path that had led to the summit where I found myself that day.

Nearly a decade before, a friend and I were planning a backpacking trip to the Grand Canyon – a last-hurrah escape before the birth of his second son. But somewhere in our reference material I had stumbled across a description of a place nobody knew: Grand Gulch, on Cedar Mesa in southeast Utah. First we were intrigued and then we were committed: this would be where we would explore the desert, far from the crowds of the famous national park.

Grand Gulch below the Bears Ears

Grand Gulch below the Bears Ears

That fall, a three-day backpacking trip changed our lives. Our flights to the southwest were some of the first after 9/11, and when we entered the canyon we left behind a world that was gripped by chaos. Serene and mysterious, Grand Gulch was a world apart.

Sandstone Arch

Sandstone Arch

Compared to grey, soggy Seattle, the sun-seared canyon country was like nothing we had ever seen. Despite years of outdoor experience in the Pacific Northwest, we were desert neophytes, making rookie mistakes that we would laugh about for years afterwards. We scoured canyon walls in desperate search of a spring, an imagined fountain of clear water bubbling from the rock. For several wasted hours we slogged back and forth across a muddy pool before realizing we were standing in our drinking water.

Canyon water

Canyon water

The overall mystery and wonder of the place was only enhanced by its archaeological treasures. Years later I learned the German word ruinenlust – literally, the joy of ruins – and nodded in recognition for what I’d felt on that trip. As The Guardian newspaper explained,

We do not simply stumble across ruins, we search them out to linger amid their tottering, mouldering forms – the great broken rhythms of collapsing vaults, truncated columns, crumbling plinths – and savour the frisson of decline and fall, of wholeness destabilized.

Although The Guardian was reviewing an art installation at the Tate Britain Museum, this description applies just as elegantly to the canyons of Cedar Mesa, where the “truncated columns” and “collapsing plinths” could refer to both the eroded sandstone of the canyons themselves and the ancient Anasazi structures harbored within.

Ruin on the rock

Ruin on the rock

The canyons placed a magic hold on us that we could not dispel. My friend and I vowed to return every year, no matter how difficult that proved in the face of his growing family. On subsequent trips we visited countless dusty canyon corners to chase their hidden secrets. We had been reborn as “desert rats.”

My wife, too, had been enchanted by the desert southwest during a rotation on the Navajo Reservation as a family medicine resident. Just one year after our wedding, she was offered a job at another Navajo town. Most people would be hesitant to make such a move, but we jumped at the chance to live in the middle of the landscape that had so forcefully captured our imaginations.

After relocating, I found my way back to Cedar Mesa as a volunteer ranger at Kane Gulch. That posting led me to the summit of the Bears Ears in the spring of 2010.

Many people consider Kane Gulch the crown jewel of BLM volunteer assignments. Our small team lived off the grid in a series of cramped trailers behind the ranger station, yet life was idyllic there. With a philosophy that rangers should actually “range” in the backcountry, I went out on patrol for days at a time, never seeing another soul.Cedar Mesa was like a living treasure map at my doorstep, just waiting to be explored.

Kane Gulch Ranger Station

Kane Gulch Ranger Station

Indelible experiences came one after the other, which still thrill me to think of them: finding a necklace shell fragment buried in the dirt, hundreds of miles from the nearest ocean and evidence of a vast ancient trading network; spending my 40th birthday camped solo beneath a millennia-old art panel, where it was impossible to feel anything but young in comparison; discovering a hidden passage at a place that I had visited multiple times but had never looked at in just the right way.

Other, darker moments stick out for me too: foolishly climbing a tricky route and getting stuck on a narrow ledge where the only way out was to take an uncontrolled slide down the wall; stumbling on the rim of a yawning abyss, inches away from a fatal drop; and helping to extract the body of an old man who had loved Cedar Mesa so much he had decided to come there to die.

I understood his unwavering devotion to the place. And as I saw the number of visitors steadily increase and the secret sites exposed on the Internet, my concern for its future started to grow. Over just a few years the changes were evident, with no sign anything was going to counter the threats. There was also renewed talk of federal protection as a National Monument, politicized stirrings that had been around for decades but suddenly seemed to take on a new urgency.

Fearing for the future of Cedar Mesa, I had lunch one day with a leading southwestern archaeologist to hear his thoughts. He had been one of the first rangers at Kane Gulch – an actual paid employee of the BLM – leading a team of armed patrolmen on horseback in the 1970s. The stories he told of Cedar Mesa were of a place foreign to me, unconnected to my own experience. Most striking were his stories of frequent, tense confrontations with looters and of planeloads of illegal artifacts flown out at night from an airstrip on the mesa top.

For him, Cedar Mesa had been lost long ago, its magic dissolved by all those planes full of stolen relics he had been unable to stop. His sadness for what had been lost and cynicism about the present situation were depressing; the dark cloud he cast over me was difficult to disperse.

Cedar Mesa view from Valley of the Gods

Cedar Mesa view from Valley of the Gods

Yet after some reflection I realized there was still cause for hope. Even though I had arrived at Cedar Mesa years after it had been lost for him, I had still found plenty of magic of my own.

I had to give up working as a ranger with the birth of my sons; there was no way to be gone for weeks at a time with two toddlers at home. Now, I watch the transformations taking place at Cedar Mesa from afar, and hope that one day my sons, too, can look up at the Bears Ears, hear their mysterious summons, and answer the call. Whether or not it becomes part of a new National Monument or the land status changes in other ways is hard to predict. But no matter what happens, hopefully others can still find their own magic on Cedar Mesa long into the future, however different it might be from the past.

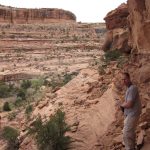

Author Andrew Weber on one of his many trips to Cedar Mesa

Author Andrew Weber on one of his many trips to Cedar Mesa

Read the entire The Battle for The Bears Ears series:

- Part I: The Legislative Landscape

- Part II: The End of Obscurity

- Part III: Road Wars

- Part IV: The Trouble With Archaeology

- Part V: A Personal View