Most of us have a list of exotic, dangerous, ambitious, and even mysterious items we want to do before we kick the proverbial bucket. On a recent trip to explore the canyons of Cedar Mesa in southeast Utah, I was able to cross one trip off: the notorious Black Hole of White Canyon. We were thoroughly prepared for what the Black Hole had to offer, which falls somewhere between dangerous and mysterious, but I wasn’t sure we were going to be able to pull it off. If it had just been my buddies and me out there, I’m sure we would have made the push even in less than ideal conditions, but I was with my two high school-aged sons and my wife had made it explicit that I wasn’t allowed to come home if anything happened to them. Let’s just say I was taking extra precautions.

Upper White Canyon which feeds into the Black Hole, photo by Bryce Stevens

Upper White Canyon which feeds into the Black Hole, photo by Bryce Stevens

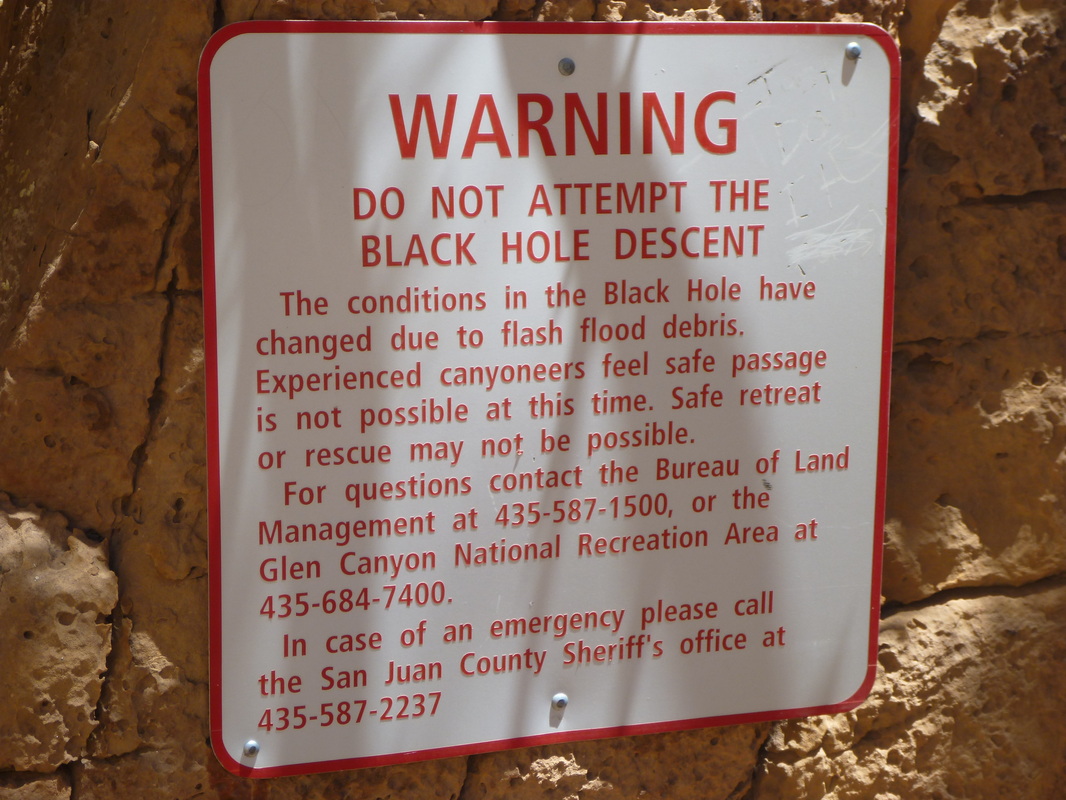

It was monsoon season in the Colorado Plateau – a period from July to September when afternoon thunderstorms can dump inches of water across the barren landscape and flood the narrow canyons in seconds. The night before our last full day in the region, we camped on high ground at the head of the White Canyon. Throughout the evening, I climbed atop my truck to peer over the pinyons and junipers and scan the horizon for potentially dangerous downpours; I was nervous. But as the desert grew darker and calmer, any potentially ominous thunderheads had dissipated. The forecast from the ranger at nearby Natural Bridges National Monument was favorable – for the first time in days – so it seemed that our risk of flash flooding was low.

Hiking deep in the Black Hole, photo Dave Riggs flickr

Hiking deep in the Black Hole, photo Dave Riggs flickr

For fifteen years I have been coveting the Black Hole which gets its name from the dark sections where light is low and water is cold. When I began exploring southeast Utah in 2001, the Black Hole kept coming up in my research of slot canyons. However, I had read an account of a flash flood that hit the canyon in 1996 while a group was exploring inside. One of the hikers was unable to reach a high ledge and the rushing water swept her away. Her father watched in helpless horror as the flood consumed the canyon. She was found dead the next day.

That tragic account and my own encounters with torrential rains in the region were enough to keep me from attempting it, but two other factors were equally as daunting. In the mid-2000’s, there was a huge log jam in the canyon that was nearly impassable. Ropes were advised for some of the canyon descents and to navigate the loosely-packed log jam. The jam had since been cleaned out by larger floods, however, giant logs were still wedged in spots around the canyon and another jam wasn’t out of the question. The other challenge was the fact that about half the canyon is very narrow – only a few feet in some sections – and filled with deep, muddy, frigid water. So, you also need a wetsuit for long swims and gear that is either submersible or accompanied by a floatation device.

One of the Black Hole swimming sections, photo Dave Riggs flickr

One of the Black Hole swimming sections, photo Dave Riggs flickr

We packed lightweight “shorty” wetsuits and decided to leave any water-phobic devices or gear in the truck; no phones, cameras, GPS or Spot satellite – useless in the deep canyon anyway – or anything that wouldn’t enjoy an icy mud bath. All of our food was either double bagged in ziplock bags or in factory-sealed containers and we carried a surplus of drinking water in durable Nalgene bottles. We wore ragged old running shoes and only had a few other essentials: a first aid kit, a short rope segment, and a knife. We were lean and ready.

The description of the route is fairly simple: enter the canyon, go downstream, and climb out. The entrance and exit are shown on the map above but aren’t obvious. Finding the descent from the parking lot is much easier than finding the exit, which is marked with rather inconspicuous cairns. Looking at satellite images ahead of time is important to have a sense of the route into the canyon and back out to the parking lot. If you don’t have two cars for a shuttle (or a stashed bicycle), then you’ll have to walk back to the car in the shadeless desert for two miles. The hike through the meandering canyon is probably only four miles, but it takes five or more hours to get through. Some sections require a little extra time to problem solve and there are fixed ropes in at least two spots to assist with hairy down climbs. I am a strong climber and I absolutely needed the fixed ropes for safety. Water levels appeared low on our trip, so some of these descents were probably longer than usual. In a few sections, there is a rock route and a water route; I often found my way up onto ledges while my companions swam below me. If you attempt this trip and see flowing water in the canyon, do not proceed. Period.

Our trip was a success in many ways. Of course, for me the main achievement was getting through it without rising waters or any injuries, meaning I was still welcome at home. And while my boys have experience exploring desert canyons in the Four Corners Region, this narrow slot canyon was novel and unforgettable. I have been planting the seeds of adventure with my boys by taking them from glacier-covered volcanoes to killer single-track trails to red rock canyons. The unique experience of the challenges of the Black Hole – slippery rocks, cold swims, and careful navigation – left a lasting impression that will, hopefully, draw them back year after year.

Landmarks on this map

|

Black Hole Entrance |

|

Black Hole Exit |

|

The Black Hole Canyon See details |