Tips for Creating and Maintaining Long-Term Motivation

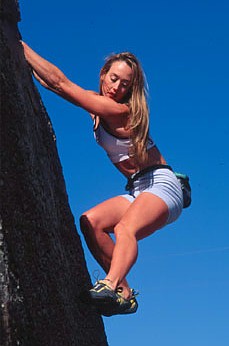

If you are reading this blog, then you are likely as passionate about climbing as I am. Still, it's not unusual to occasionally experience a drop-off in motivation, despite your love of climbing—do any activity on a regular basis for a long enough time and you will eventually experience periods of low motivation. Often times, such a lapse is simply the result of mental or physical fatigue, perhaps following a hard day at school or work. Such temporary motivational troughs affect us all from time to time, and they are something that you just need to push through. If you can prod yourself to the gym or crag and climb a first route, chances are you will snap out of the funk into a more energetic, positive state. So, the antidote to short-term motivational lapses is simply to muscle through it—get forward momentum started, and in a few minutes you’ll likely be cured.

If you are reading this blog, then you are likely as passionate about climbing as I am. Still, it's not unusual to occasionally experience a drop-off in motivation, despite your love of climbing—do any activity on a regular basis for a long enough time and you will eventually experience periods of low motivation. Often times, such a lapse is simply the result of mental or physical fatigue, perhaps following a hard day at school or work. Such temporary motivational troughs affect us all from time to time, and they are something that you just need to push through. If you can prod yourself to the gym or crag and climb a first route, chances are you will snap out of the funk into a more energetic, positive state. So, the antidote to short-term motivational lapses is simply to muscle through it—get forward momentum started, and in a few minutes you’ll likely be cured.Long-lasting motivational doldrums, however, are more deeply rooted and require more fundamental changes to snap out of. In some cases, a persistent lack of motivation signals a growing dissatisfaction with your climbing. For example, a sustained plateau in performance, a steady rise in frequency of frustration and failures, or a feeling of persistent pressure to perform can all lead to diminished motivation. Another possibility is that the drop in motivation is the result of overtraining, as your mind and body begin to run aground. More common, however, decreased motivation is simply the result of a stagnant climbing routine. If you do any activity in the same way, with the same people, at the same time, week after week, it will become monotonous and unexciting. If any of this sounds familiar, I’ve got three prescriptions for pumping up your motivation.

Strategy #1: Set Some Compelling Performance Goals

The most common type of performance goal is a desired climbing grade to achieve. This month it may be “to climb 5.10”; next month it may be “to boulder V4”; next year it may be “to redpoint 5.12 or boulder V7 or whatever. Similarly, you can set training goals that will pique motivation to achieve the physiological changes you desire. For instance, you might set a goal “to do ten or twenty pull-ups” or “to lose five pounds.” Finally, there are ticklist goals; that is, a to-do list of boulder problems and climbs. To sustain and maximize motivation, it helps to have a written ticklist of climbs you want to send, both in the short-term (say, in the next couple of weeks) and in over the entire climbing season ahead. This way, each send—whether it’s this week or next month—with create what I call “achievement inertia”, and with each success your motivation will get recharged and propel you onward.

Strategy #2: Begin a Targeted Training Program

During your first few years as a climber, you will realize (or have realized) steady improvement simply by climbing a few days per week. These initial rapid gains in ability result mostly for learning the fundamental technical and mental skills. As you continue to advance in ability, however, the improvement curve begins to level off as physiological constraints come to light. This is a common and extremely frustrating situation that most climbers face at some point, and it can destroy motivation as your improvement on the rock becomes imperceptible. Fortunately, most physical constraints can be shattered with an intelligently designed, targeted training program.

Now while detailing a training program is beyond the scope of this article, I will give you a few tips to get you started on the right track. First, it’s important that you recognize that the most effective training program for you will be one that is designed to train-up your weaknesses. Therefore, it’s vital that you correctly determine your greatest limiting constraint. Is it lack of lock-off strength, lunging power, local forearm endurance, or perhaps something more subtle like poor hip flexibility or lack of contact strength. Acute self-awareness and the ability to objectively self-assess is essential. Begin by taking a self-assessment test, such as the ones contained in my books How to Climb 5.12 and Training for Climbing. It’s also useful to watch some video of yourself climbing—perhaps you’ll discover that your limiting constraints are actually technical, not physical. Of course, you could also enlist the help of a climbing coach. An increasing number of gyms now have a qualified coach on staff, so I encourage you to consider this option.

Regardless of your source of guidance or the program details, it’s important to create a written plan of action that will dictate a firm, long-term workout strategy. Irregular or haphazard training programs will produce mediocre results at best and may even lead you down the wrong path of action. You are better off just climbing as training as opposed to launching into the darkness of trial and error. The bottom line: Do your research, design an appropriate program, and then commit to executing the program long-term. This is the prescription for an uncommonly effective training program that will grow both increased fitness and motivation.

Strategy #3: Tap into the Human Resource

While the social and often crowded nature of a climbing gym or crag possesses many potential distractions, it’s important to recognize the tremendous human resource that is present. People are the ultimate catalyst for adding new life to your climbing, and the simple act of climbing with a new partner will spark motivation and increase enjoyment. Use this as your incentive to reach out and open up to strangers, even if it’s not exactly in your nature to do so. Make it a goal to rope up or boulder with one new person every week or two, and you’ll discover a new kind of excitement and energy for climbing.

Subscribe to Eric's RSS Feed

Subscribe to Eric's RSS Feed

Subscribe to Eric's RSS Feed

Subscribe to Eric's RSS Feed