Finding the Lost City of the Lukachukais

Lost cities don’t exist. They are confined to the bottoms of oceans and 19th-century jungles. As children, we all eventually give up on looking for buried treasure in backyards, or undiscovered, ancient ruins down the block because at this point humanity has been around long enough to stumble over most of them. Long before I even started exploring the backcountry, I had dismissed any notion that there were lost remnants of civilizations out there. But in the fall of 2009, I discovered there are still blank spots on the map (relatively undocumented throughout history) when a group of us found one of them in, of all places, Arizona.

There’s a tacit code of etiquette surrounding Anasazi ruins: you don’t take anything, you don’t tell anyone how you got there, and you preserve this outdoor museum as long as possible.

Marching around the floor of the Summer Outdoor Retail Show in Salt Lake City, my then boss, Bryce Stevens told me about a secret trip he was planning with a Trails.com co-worker, Andrew Weber. Together they had written guidebooks, explored all over the northwest, and wore wool socks even when they didn’t have to. Now they were planning a hunt for a massive Anasazi cliff city that only a handful of anglos had ever seen. It was aptly named, The Lost City of the Lukachukais.

“I want you to come with us,” Bryce told me.

I had been working for him for a little over two months. He and Andrew had been good friends for years and traveled to remote canyons in the Four Corners region many times. I was a new satellite employee who had met each of them in person just once. While the prospect was exciting, there was no conceivable reason why they would want to drag me along.

When I confessed as much, Bryce put a finger in my chest. “You climb,” he said. “What do you know about the Anasazi?”

I had a vague memory of visiting Mesa Verde as a child and reading a Tony Hillerman novel in eighth grade about pot hunters.

“Tons,” I told him.

“Good. We’re going at the end of September.”

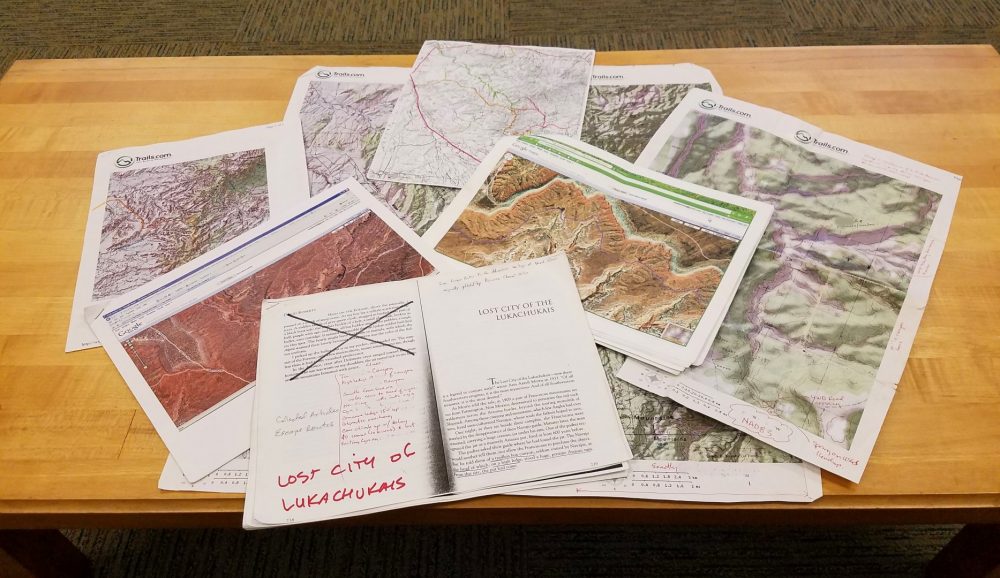

There were to be four members on the trip: Bryce, Andrew, their good friend Dan, and then me – the other guy. As the trip grew closer, it seemed impossible that my invitation had been legitimate. These three friends had clearly done their research; they owned books about Anasazi ruins all over the Southwest, they had detailed notes written in the margins, they had satellite images of likely Arizona canyons, they had done this kind of thing before. I watched emails fire back and forth with my named cc’d about washed out roads and alternate routes. They planned food, tents, gas stops, stoves, the car rental, approval to be on the Navajo Reservation, and all the necessities for not only success but survival. I jumped into the thread, if for no other reason than to remind them I was accidentally still involved.

What would you like me to bring? I asked.

The response was short:

Rope. -Bryce

Maps, aerial photos, and research on the Lost City

Maps, aerial photos, and research on the Lost City

Now I am not a world-class rock climber. I am a mediocre climber who sticks mostly to bouldering and sport routes who talks a mean game about his ability among people who will likely never see evidence to refute it. Bryce had never seen me climb before inviting me, but I likely bragged about it in front of him, and by the time my plane touched down in Albuquerque and I met up with the other three, it was clear I was here to scale something no one else wanted to.

We all climbed into a rented 4WD Dodge Nitro and tore off into the desert of New Mexico, through clusters of trailers with tires on the roofs and hogans with no windows. Fragments of both Navajo and Anasazi culture popped up on the roadside and disappeared behind us, filtered and polished by modern Americana. Kokopellis danced over restaurant marquees. Motels showcased handprints on their walls. Locals sold turquoise under homemade signs. Then, gradually everything gave way to a large expanse of nothing disrupted only by lava rock jutting out of the scrub brush like the spine of some malnourished cow.

The few documented accounts of finding the city are intentionally vague. There’s a tacit code of etiquette surrounding Anasazi ruins: you don’t take anything, you don’t tell anyone how you got there, and you preserve this outdoor museum as long as possible. Ruins are scattered all over the Four Corners in the maze of canyons that make up the Southwest. You can stumble upon cliff art or an arrowhead without meaning to. These relics of an ancient civilization exist on their own out there and that’s thanks largely to everyone agreeing to let them exist. David Robert’s provides the best account of The Lost City of the Lukachukai but it doesn’t offer much. The most we could parse out geographically was that it was in northern Arizona on Navajo land. Oh and he describes the entrance to the city, he said it was dangerous even for an experienced climber. Perfect.

Petroglyph watching over the Lost City

Petroglyph watching over the Lost City

Bryce and Dan had mapped out an old road with a steep vertical climb that they thought would get us to the top of a mesa so we could see the topography of the canyons better. Road was a generous word for what we drove. It was impossibly skinny, washed out, with cliff face on one side and an unforgiving drop on the other. We all winced each time the Nitro bottomed out on sandstone or threatened to tip. Bryce proudly pointed out that he had noted a dented muffler on the rental inspection sheet before we left.

Once we reached the top of the plateau the road dissolved into wash-beds and sage. We guessed at our destination based on printed satellite maps, frequently getting out to cut weight over boulders and to run ahead of the car to drag fallen junipers out of our path. By late afternoon, we reached the rim.

Scouting for a way into the canyon from the mesa top

Scouting for a way into the canyon from the mesa top

We collected our things, filled up water bottles from the jug in the car, and scouted a tributary so steep and tight that we had to drop our packs over the edge so the weight wouldn’t pull us off the rock as we scaled down. Even from the start it was slow going. The route was filled with yucca that stabbed through our pants and dusty scrub oak that stuck to the sweat on the backs of our necks every time ducked through them.

The canyon closed in on us; the farther we hiked the more choked it became until we were scrambling down loose boulders on all fours or stemming from wall to wall over vegetation too thick to fight through. The maze of dried rivulets was endlessly frustrating, leading us a half an hour down a wrong path that ended at a sheer sandstone cornice. The only water we saw was a small pool the color of tea sitting at the lip of a dead waterfall. The drop was too big to jump down and the only other option was an unpromising shelf of crumbling sandstone high on the right wall that disappeared around a corner.

Bryce craned his head around the edge, then peeled it back and laughed. “There’s a moki trail on the other side.”

“A monkey trail?” I asked.

“Moki trail. It’s carved in the wall. It’s Anasazi.” I peeked around the edge and saw the wedges cut from the rock. The Anasazi carved them all over the desert with rudimentary tools, holding themselves in place over high exposed ledges and patiently chipping away at each one. They were expert climbers because they had to be. No one knows why they stopped building pit houses and started climbing canyon walls to build their cities but the going theory was protection against enemies. A thousand years later, we were using their route.

Long after we lost sunlight over the walls and just before dark, the narrow canyon released into a larger valley and we were finally free to scramble in something other than a single file. We set up camp just above the wash and poured water over freeze-dried meals in the darkness, watching the moonlight seep down a far wall.

The Navajo believed that even handling the bones of the Anasazi could cause untold damage to a person, as well as his entire family. Taking anything from the ruins could be just as destructive.

Andrew and Dan filled me in on the disappearance of the Anasazi. The unanimous exodus of the people was sudden, the equivalent of a whole city and its suburbs getting up from the dinner table and walking away forever. They talked about the Anasazi cliff art that was meticulously chipped out of rock because a few Navajos were concerned they had the power to curse. The Navajo believed that even handling the bones of the Anasazi could cause untold damage to a person, as well as his entire family. Taking anything from the ruins could be just as destructive. The name “Anasazi” is Navajo and is usually translated to “Ancient Ones” but the more literal and accurate translation is “Ancestral Enemy.”

When I woke up the next morning, Andrew was already out of the tent, I could see him through the unzipped rain fly with his tripod set up, taking pictures of the sunless canyon. “It’s cold,” I told him.

“Give it an hour,” he said. True to his word, the sun filled the canyon as we ate and it was suddenly unbearable to be in anything other than a t-shirt. We packed up day packs with empty water bottles and iodine tablets and headed in the opposite direction from where we assumed the Lost City might be. We burned through most of our water the previous day and needed to find a source before any more exploration.

Descending the trail-less tributary canyon

Descending the trail-less tributary canyon

Throughout the morning and into the afternoon we searched. We checked up dusty tributaries, climbed up onto stained shelves, and scoured the wash but we couldn’t find any evidence that water had even existed here. In the late afternoon, we split up, desperate to find something we could fill our bottles with. I trotted up a pile of loose rocks to what looked like it might be a seep through the wall of the canyon. Dying, brittle moss surrounded the crack, flecked with sand from a recent wind. I kicked at the dirt below for any signs of mud and jumped when I saw the head of an animal peek out from under a rock. It was an infant kangaroo rat, eyes half open. It either wasn’t afraid of me or too sick to move. I scanned the area and saw another, lying dead in the sand less than three feet away. I took off my pack, tore at a bagel and doused it what little water I had left. I placed the soggy bread next to the live rat’s head. It smelled the food in slow movements, but it didn’t eat. It was probably too young to eat anyway. It just sat there, shaking and looking at me.

The branches of a nearby bush snapped and all the foliage started to shake. I couldn’t see through the scrub oak so I called out, hoping it was someone else coming up to check on the seep. The shaking stopped, then continued after a period of silence. I could hear the footfalls in the dirt, heavy and stumbling. It was something big, and possibly drunk. I inched backward, trying to determine how quickly I could run/fall down the boulders. Then it mooed.

“Cow!” I yelled.

“What?” I could hear Andrew down in the wash below me.

“There’s a cow. A really big cow. It’s a… it’s a zoo up here.”

There was a pause while the cow ran full tilt in the opposite direction. “Sounds like an awful zoo. Is there any water?”

“No.”

“Alright, come back down,” he sighed. “We have to get out.”

We walked back to camp and did an inventory of our water reserves. Half a bottle each, barely enough to get out.

“We are getting close to a dangerous situation,” Andrew said.

Bryce looked up the canyon, where we expected the Lost City to be less than three miles away. He turned back toward us and nodded. “Yep. We need to go. Let’s pack up, we’ll probably reach the car by dark.”

The way out was worse than coming in. Everything we slipped or jumped down before, had to be scaled now, which was only made more difficult by the dehydration and general disappointment. After an hour, we were half way up the tributary and completely out of water.

“If anyone gets really thirsty, I have apples,” I offered.

“Save them for the car ride,” Dan said. “It would be bad news if we got stuck in the car somewhere without anything.”

Less than a mile from the mesa rim, we were forced to negotiate the steep hand-to-toe moki trail again. If anything, at the time it seemed like just another obstacle, we didn’t entertain many ideas about its purpose. We didn’t, until we rounded the corner and saw the stagnant puddle again.

It hit us all at the same time. The moki trail was a water trail. We had traipsed all over the valley floor, likely across the same footsteps of the ancients looking for water and this trail led us to it.

The only water in the entire canyon

The only water in the entire canyon

The water immediately clogged the filters and made pumping slow going. What drizzled out the other end into our water bottles looked like it had leaked out of a rusty pipe. I held a full bottle up to the dying sunlight then dropped an iodine tablet in for safe measure.

Our mood gradually shifted from anxiousness to enthusiasm. We were close to the rim, and the car, and whatever the mesa was using instead of a road. But we also still had two days to burn if we wanted them, and water. We could camp for the night, wake up early, fight down the tributary again and hike straight to the city. We talked it over until Andrew said, “If we don’t do it now, I don’t think I would ever come back here,” and we all nodded in agreement.

We considered sleeping on the hard sandstone, but Bryce scouted an alcove not far from the puddle. The scramble up into the pocket was arduous, but the location was perfect; a pocket carved from the wall with a bed of loose sand.

“Well, this is a very Anasazi moment,” Dan said as we unfolded our sleeping bags. While we ate, Bryce talked about our plan for the City the next day. He was bouncing with excitement. He knew we’d been given another chance to see something very few people had and that it would be a colossal disappointment if we couldn’t get into the ruin now. I sweated and stirred my chicken noodles.

The next morning was hot but the alcove stayed dark long after the sun was up. I filled a daypack with the rope, my climbing shoes, and a few slings before heading down the tributary for the third time. By now we could predict where the hard parts would be, we could see our footprints going in each direction, we started to know the twists and turns. We developed a relationship with the canyon, and for Bryce, it was an abusive one. He uprooted wobbly rocks and shattered dead branches that hung or fell into our path, sometimes yelling at offending vegetation.

Early light hitting the walls of the canyon

Early light hitting the walls of the canyon

We made good time into the valley but the day was already roasting. We walked the floor of the canyon where we hoped the city would be and around 11:00, we rounded a corner and the cliff city revealed itself like the Bates Motel. Expansive and looming over the rest of the canyon, it filled the entire alcove, well preserved, and at least 100 feet off the ground. No easy routes in.

We spread out and started hunting for the best scramble. Bryce scouted a crack up the western wall that featured a very brief but very real overhang, while Andrew and Dan dipped around the far corner to see if there was a way to traverse from higher up the canyon. I walked directly up a sage covered hill below the City, scanning the wall for a route on which I couldn’t picture myself dying. At the top of the hill rested a series of boulders that had fallen away from the wall over time. The giant rocks were each the size of a compact car and carved into the face of one were tiny carved out pockets like shallow eyes. The pockets were man-made, diagonally justified, just right for climbing. I scanned the wall where the slab had broken away from the rock face. I shielded my eyes from the sun and craned my neck to see above it. There, just past the gap, were the remnants of a hand-to-toe trail leading directly up into the city.

“It’s here,” I shouted.

“Does it go?” Bryce asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “It goes.” I scouted the route, trying to determine exactly where I would place each hand and foot on the way up. The climb was only around 70 feet to the top, but it drifted to the left, over a much more sizeable drop down to the canyon floor. The hardest part would be climbing the jagged piece of face missing the few holds that now sat useless on the ground next to me. Everyone hiked the hill, sucking water in the heat as I put on my harness and tied into a rope that couldn’t protect me. No one spoke which was polite but not comforting by any means. I started climbing.

Author reaching the top of the climb

Author reaching the top of the climb

On the way up, I kept my mind occupied with thoughts of what it might be like to fall and die. Or fall and break my leg out in the middle of nowhere and die a few days from now. “Fuck,” I mumbled.

“Rock? Did you say rock?” Bryce asked. I looked down behind me to see the three of them shielding their faces from whatever I had announced was falling.

“No, sorry. Just talking to myself.”

The first part of the climb was sparse and dusty, caked in a century of sand. I had to wipe my hand on my shirt after grabbing each new hold. I took it as slow as possible, calculating each move before putting weight on it, knowing the full and literal gravity of the situation. Within three minutes I was surprised by the moki trail and after that it was an easy scramble to the top. The rope wasn’t long enough to anchor from anything substantial and still have both ends fall back down to the group, but I could set up slings on a juniper and belay everyone from above.

I was so excited to not be dead or injured I forgot to even look toward the ruins but when Bryce, Andrew, and Dan were up, they didn’t bother taking off their harnesses before drifting, open-mouthed, into the City. The first thing I saw was the pottery. Sherds littered the ground, each one the size of a sticky note with intricate black and white designs, or gray with tactile prints painstakingly pressed into the surface. I found a completely intact lid to a clay pot with a decorative handle. Scattered throughout the pottery were petrified ears of corn and chert flakes from arrowheads. The Anasazi’s tools, dishes, and food last used around 800 years ago, still there.

Pot sherds and other items scattered about

Pot sherds and other items scattered about

The other three were already exploring the rooms. I sidestepped around freestanding walls, and ancient wood beams hanging over collapsed kivas. We stuck our heads into perfectly intact rooms and waited for our eyes to adjust to the darkness. Inside were shelves, smoothed sandstone tools for grinding corn, and an ancient pestle. It’s hard to determine how many rooms this large alcove once contained as some are just piles of rubble, but it could be as many as 40 rooms.

Well preserved rooms with roofs still intact

Well preserved rooms with roofs still intact

I walked toward what looked to be a square hole in the ground and Bryce stopped me with his hand. “You don’t want to walk on that,” he said. Dan poked his hand out of the hole and waved. We eased around it toward the back of the alcove where we found an easy entrance. The inside was unbelievable. The room was completely preserved. Fired-wood beams holding it all up, benches inside cut from stone, a fireplace with its own chimney. It looked exactly as it must have looked when they used it, but with thin layer of mouse scat over everything. We could stand up perfectly straight inside and we did, for a long time, trying to understand exactly what we were experiencing. We were all exhausted, hot, and disbelieving we were actually here after giving up the day before. It was hard to grasp the greater historical context of the moment, still we tried.

Dan waving from inside a hidden kiva

Dan waving from inside a hidden kiva

“We did it. We found it,” someone would say.

“Yep,” we would all nod and watch the dust catch in the light from the hole in the ceiling. We wandered around looking in other perfectly preserved kivas and rooms, scanning the rock art on the walls and the pottery littering the ground. Even the crumbling walls revealed items long buried. I found a bracelet woven out of yucca and what looked to be human hair. One particular piece of pottery caught my eye because it was pure white, unlike any piece I had seen previously. The inside of the concave sherd was the same bleached color as the outside and contained ridges in no particular pattern. It wasn’t until I saw the tiny pores when I examined the edges that I dropped it back on the ground and backed away. Andrew and Dan paused from clicking photos to watch me stumble backward like I had stepped in a spider web. “What did you find?” Dan asked.

“Skull, I accidentally picked up some skull.”

“Really?” They both squatted around it. “Oh yeah, wow. I wonder if they’re all from the same person.” Andrew pointed down toward the sloping edge of the alcove where a set of human femurs rested precariously on the rim, blanching in the sun. I climbed down and put my face close to them, trying to imagine them constituting a human at one time. We explored for over an hour, and spent just as much time resting and looking out at the serenity around us.

Woven items have not disintegrated in this dry environment

Woven items have not disintegrated in this dry environment

I stood next to the clay and rock walls, wide-eyed, sliding my fingers into the dried prints left by the Anasazi who packed it into place. This was unlike any museum or any trip to Mesa Verde. There was an overwhelming sense of limitlessness here. Of being able to not only see it up close, but touch it, crawl into it, to pick it up with reverence and put it back in place. This ruin had not been excavated, restored, cleaned up, or worn away by heavy traffic. We were incredibly lucky to not only find it, but to be alive while it still existed, intact, untouched and forgotten for centuries. Someday the slabs of rock hanging over it would crumble and destroy it, or bury it forever, but we beat that bit of history, I got to slide my fingers through the fingerprints of the Anasazi.

One of up to 40 rooms that once stood in the Lost City

One of up to 40 rooms that once stood in the Lost City

When we started getting low on water, we put everything back we had touched or moved and retraced our steps through the canyon. We made it to the car about an hour before dark and started driving. The path out, a different one, was just as rough as the way in. Andrew, Dan and I walked ahead of the car for most of it, scouting out washes up ahead or filling in deep ruts. We drove slowly through the darkness until the road condition started to improve. Eventually we could see the lights coming from a distant town. Listening to the only DJ on the radio speak in Navajo and play country music while smelling the burning sage caught in the undercarriage I tried to let it all sink in. This wasn’t supposed to happen; errant bragging had afforded me a once in a lifetime opportunity. I didn’t deserve to be here, and I just hoped they would never realize it. These three men weren’t interested in being renowned for finding a lost city, or excavating it for priceless artifacts, or even writing about it. They just wanted to see it, and I’m insanely lucky for getting to share in that.